The Cabinet of Curiosities

‘Ye Ark’

The Museum or Cobbe Cabinet of Curiosities at Newbridge was originally referred to as “Ye Ark”. It was started by Lady Betty Cobbe (1733-1806) as a room initially exhibiting her collection of shells, exotica, and curios. Lady Betty collected a vast array of nautical apparel from the Dublin markets where merchants and sailors would sell such shells, coral, sponges, mother of pearl and other exotica to the wealthy elite fascinated by these objects. Over the years successive generations of the Cobbe family have greatly expanded the collection to the wealth of material seen on display today.

‘Cabinets of Curiosity’ or wunderkammers were early modern treasure troves within palaces and private houses dedicated to the display of the material world. These rooms attempted to showcase the wonders of the natural world. While often idiosyncratic to the collector’s taste, objects within were usually categorised into the three historic divisions of the natural world; animal, vegetable and mineral. Today the few remaining cabinets reflect historic attempts to interpret the materiality of the world in a nuanced humanistic manner. They also reflect the growing appetite for collecting and a universal fascination with the natural world.

Shells have been used over the past centuries variously as currency, food, tools and ornament. Collections of shells are known to have existed at least 2,000 years ago with samples having been found at the Pompeii excavations. With the expansion of the discovered world from the sixteenth century, wealthy and learned people could amass for themselves collections of shells, often for no purpose other than decorative. By the eighteenth century Lady Betty Cobbe’s collection of shells was unexceptional in a house of the scale and status of Newbridge. From the time of her marriage Lady Betty was purchasing shells in Dublin, Bristol and London. This large collection of shells was arranged decoratively and not ordered in any way other than by size or shape to give a pleasingly organised appearance. Most shells mainly originate from the Indo-Pacific and south Atlantic regions. Intermixed amongst the collections are a number of shells from Britain and Ireland, many presumably collected from the local beaches of Donabate, Portrane and further afield. As Kathie Way writes ‘It would be pleasing to think that all these were collected by the Cobbe children for the museum’.

While Frances Conway (1777-1847), the wife of Charles Cobbe (1781-1857) is not very well represented in the Newbridge archive her mark was certainly left in the work she did in collecting for and organising the museum at Newbridge. Frances seems to have taken ownership and a particular pride in organising new and historic additions to the collection, often referred to by her children as ‘mother’s museum’. After her death it had fallen into a state of neglect being referred to by her daughter in 1858 as ‘the poor old museum’.

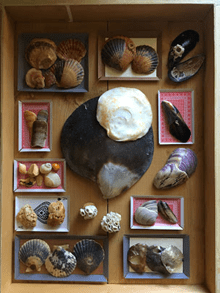

Frances was presumably the one who initiated the project of crafting small ornamental display trays and holders from patterned paper, embossed card and most thriftily lids with trade labels and disused playing cards. This early form of recycling was hand crafted by Frances Cobbe along with the fabricated boxes and trays, delicately embellished by hand for categorising the shell and mineral collection.

A leaflet on display in one cabinet advertises the auction of the ‘Oriental Museum’ of Col. Thomas Cobbe in 1838. Thomas was the younger brother of Charles Cobbe and served in the East India Company. He married Nuzzear, an Indian begum, and together they had ten children. Thomas then retired from service in 1836 and was sailing back to England when he died suddenly and was buried at sea. The ‘oriental collection’ of souvenirs from a thirty-year career in India was thus auctioned by his older brother Charles in other to finance the care and education of the children.

‘ the most special room of all is the Museum of Curiosities..this is a rare example of that prevailing 18th and 19th century tradition of the gentleman natural scientist at work, carrying on a practice established in the 16th century of assembling a “cabinet of curiosities” or a private museum featuring mineral, rock and shell specimens.’

The original wallpaper of the room was oriental silk pinned onto the wall with faux bamboo trellising. Most likely bought from a Dublin paper merchant it depicted exotic scenes of oriental life. It was taken down and sold in the 1960’s by Mrs. Cobbe. She had the museum cabinets removed and converted the room into a private sitting room. Luckily the original cases survived in the vacant basement rooms and when the council opened the house to the public, they could fully restore the museum. It was then that the current wallpaper was replicated from memory by Alec Cobbe. This reinstated the original feel of the room, which now has a replica sample of the collection on display.

Many contemporary artists continue to be inspired by the wunderkammer and their exotic collections. Artists such as Jane Wildgoose, Mark Dion, and Rosamund Purcell draw on this legacy in their work today.

Further reading:

Arthur McGregor (ed.), The Cobbe Cabinet of Curiosities, An Anglo-Irish Country House Museum, (New Haven and London, 2014)

Giulia Carciotto and Antonio Paolucci, Cabinet of Curiosities: Hidden Treasures, Dreams of Universal Knowledge and Exquisite Beauty, (Cologne, 2020)